From Sumeria to SpaceX

Alex Nedelcu, Leonardo Times Editor

The ancient Sumerians made the first recorded observations of Mars.Subsequent civilizations, from Egypt to China, studied the motion of the planet and ascribed meaning to its blood-red color. But how have our views of Mars evolved? And how are our perspectives going to change in the future?

Mars has a radius equal to half the Earth’s, a thin atmosphere dominated by carbon dioxide and an utterly inhospitable climate [1]. Once, it might have been capable of sustaining life, as proven by the traces of water in solid form that were found in 2018 in polar regions. Its surface, covered in iron oxide, is reminiscent of blood, which led to the ancient Romans calling it Mars after their god of war.

Mesopotamia, China, Rome

The civilizations in the fertile crescent, such as the Sumerians, Babylonians, and Assyrians, referred to Mars as Salbatanu, explained as ‘constantly portending pestilence’ [2]. Diviners and astrologers associated Mars with the god Nergal, mighty, vengeful, and bloody. Its radiance was directly proportional to the propensity of conflict, and a faded Mars was considered beneficial for the people. Interestingly, the correlation of Mars with Nergal took on political undertones, as historians argue that this ‘false, malevolent star’ would be associated with countries that were malevolent to the diviner and therefore to the king and the land. In general, the ‘enemy star’ was associated with the geopolitical enemies of the state, wherever they were located [2].

Credit: Hatra Gallery, Iraq Museum

Two thousand years later, the Romans also ascribed Mars’ red hue to their god of war, second in importance to Jupiter. Under the emperor Augustus, Mars became Mars Ultor (“the Avenger”), his personal guardian as he avenged the murder of his uncle, Julius Caesar [3]. A prominent myth also links Mars to Rome’s founding, with the god said to have fathered legendary founders Romulus and Remus. Beyond fables, Mars was the protector of Rome’s proud military tradition and was worshipped by the legions [3]. Under his auspices, sacrificial blood flowed from the Field of Mars, and warriors died a glorious death on the battlefield.

Credit: Jean-Pol Grandmont

Further east, under the reign of the Qin, Han, and Tang dynasties in ancient China, astronomical observations were used to predict the future. Astronomers had assigned a certain subject to each constellation, and each planet corresponded to a certain element in the “Wuxing” (Five Phases) system that connected the elements of Fire, Water, Wood, Metal, and Earth [4]. Mars represented fire and was known as the fire star, characterized by conflict and fighting. In his paper on the role of astronomy in ancient Chinese society and culture, Xiaochun Sun writes that comprehensive treaties were composed to explain every possible interaction between the heavenly bodies [4]. Specifically, if Mars entered the constellation Scorpius, assigned to the Chinese Imperial Court, ill tidings were foretold for the harmony of the imperial family.

al-Qabisi and Kepler

But this wasn’t Mars’ only connection to faith and religion. The doctrine of planetary dignities, an astrological theory developed by 10th-century scholar al-Qabisi, was used to determine the strength and nature of the influence of each planet on a new child’s birth based on their location in the zodiac at birth [5]. The astrologer divided the degrees of each sign into masculine and feminine groupings, with Mars representing “tyranny, bloodshed, conquering, highway-robbery, wrongful seizure, the leadership of armies, haste, inconstancy, smallness of shame, journeys, absence”. Furthermore, in the Middle Ages, Europeans organized their lives based on the position of the heavenly bodies, with this influence shown even in the language for the days of the week: Tuesday is Mars-day (or “Mardi, “Martes”, and “Martedi” in French, Spanish, and Italian respectively) [6].

Late Roman philosopher Boethius built on the work of Plato and Aristotle to describe three categories of music, the critical one was that of the universe, with the mathematical relationships that drive it manifesting in musical qualities and tones. It was in the pursuit of this concept of “musica universalis” that Johannes Kepler discovered the third law of planetary motion in 1618. The astronomer aimed to reconcile the emerging vision of a Sun-centered planetary system with Pythagoras’ concept of “Armonia”, universal harmony [7]. Though Kepler was distraught that Mars’ orbit did not represent a circle, the archetypal symbol of perfection, the resulting elliptical orbit revealed a more subtle form of harmony. He found that the ratio between the maximum and minimum angular speeds of each planet approximated musical intervals, with Mars taking up the role of tenor in Kepler’s celestial choir. The ratios of the maximum and minimum speeds of planets on neighboring orbits yielded a complete scale – with one exception: Mars and Jupiter, which created an inharmonic ratio of 18 to 19 [7].

Aliens on Mars?

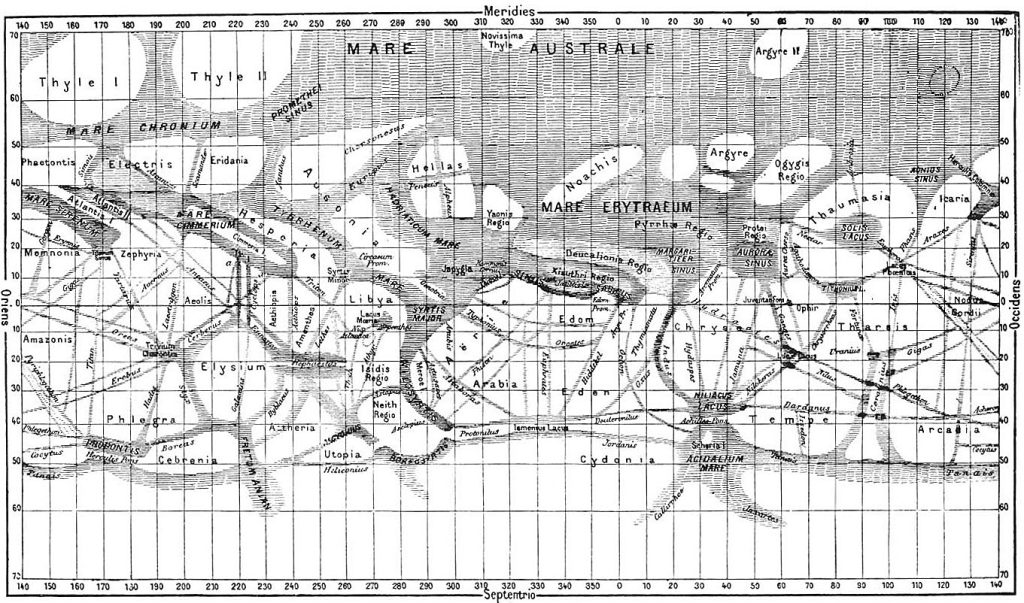

After it was proven that the Moon could not sustain life, the focus shifted towards Mars. In 1877, Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli charted the surface of Mars using a primitive refractor telescope. A mistranslation of his observations (“canali” – grooves) resulted in increased interest from the public speculating that intelligent life had dug canals into the surface [8]. Throughout the first half of the 20th century, artists created stories and images of the Martian landscape based on these observations, with H.G. Wells’ “War of the Worlds” novel being most representative of this time of excitement [9]. With near-infrared spectroscopy, Dutch astronomer Gerard Kuiper proved that the Martian atmosphere was primarily composed of carbon dioxide in 1947 [8]. Though the inhospitable climate was used as proof that no sentient life close to what exists on Earth would exist, the planet’s mythologized reputation (and a new geopolitical competition) transformed it into an inspiration for exploration and discovery [9].

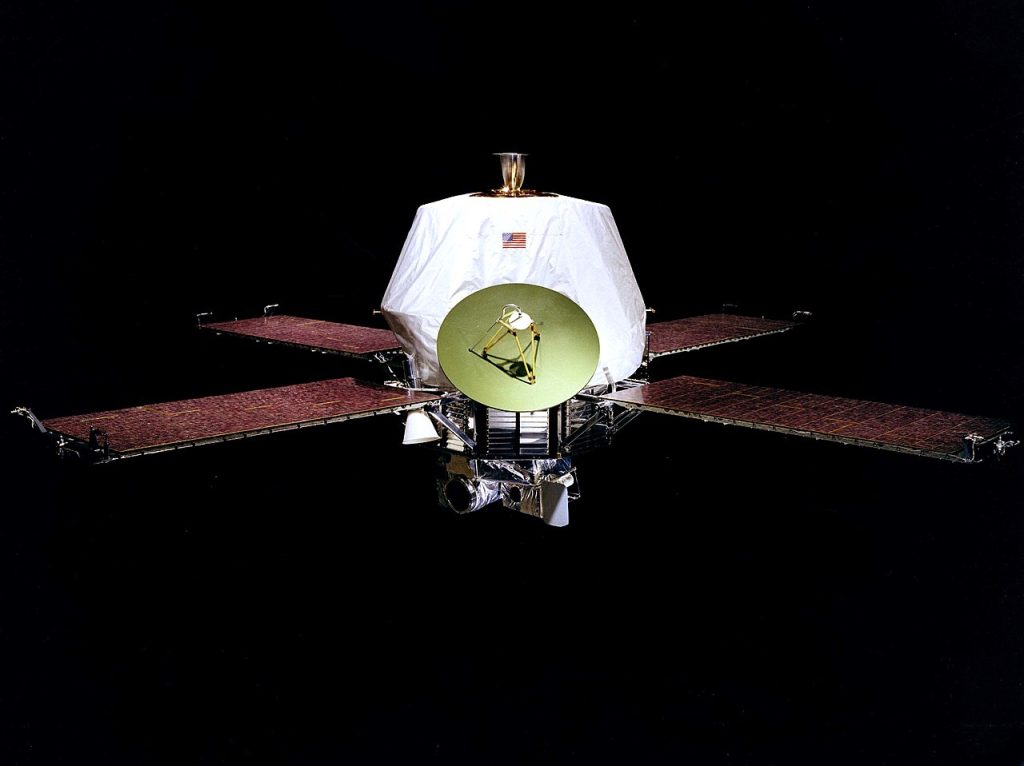

Space exploration served as a dramatic arena for Cold War competition, with the capitalist United States and the communist Soviet Union racing towards the stars. From Sputnik to Challenger, the two superpowers constantly tried to one-up each other, with achievements in space exploration being seen as sources of national prestige. Several orbiters were dispatched to Mars by both countries, with the USSR’s Mars 1 successfully attaining a payload-less flyby in 1962 and the US’s Mariner 4 famously taking pictures of the Martian surface in 1964 [10].

Though both the Soviets and the Americans attempted multiple launches of orbiters and landers towards Mars, only the American Mariner 9 orbiter and Viking lander succeeded in 1971 and 1975 respectively [10]. Each superpower independently planned crewed missions to Mars, but funding for NASA and the Soviet – and then Russian – design bureaus slowly decreased after the collapse of the Soviet Union. As Fukuyama’s so-called end of history dawned, the dream of Mars became a unipolar fantasy.

After the end of the Cold War, NASA’s Mars programme continued with the Pathfinder lander (1996), the Global Surveyor orbiter (1996), the Odyssey orbiter (2001) and the more recent Mars Exploration Rovers [10]. In the new millennium, Mars became the target of true international exploration, with European and Indian spacecraft successfully reaching Mars.

Red Mars, Blue Mars

And what about the future? It is impossible to talk about Mars without mentioning the elephant in the room. Elon Musk’s SpaceX stated their intention to deliver a crewed mission to Mars, working within NASA’s Artemis program. However, the claims made by Musk over the past decade have only materialized on a few (but veritable) occasions. For example, in 2018, he stated that SpaceX could help build a base on Mars by 2028 [11], but, even with the recent successes in Starship launches, they seem far from capable of reliably transporting everything required for a “Mars Base Alpha”. As Matthew Shindell writes in his recent book “For the Love of Mars”, in prominent political figures’ rhetoric, a trip to Mars always appears to be just a few decades away, allowing present policies to be justified indefinitely [12].

It is undoubtedly true that pushing for space exploration would spur a new age of innovation, triggering developments in propulsion, robotics and automation, structural design, and materials science, but also health and safety, governance, and nuclear engineering. Furthermore, so-called “techno-optimists” argue that the dream of Mars provides a compelling vision for the future, which could help bridge our petty divisions here on Earth [13]. Quoting Buzz Aldrin, “If we can conquer space, we can conquer childhood hunger.” Perhaps Mars will be the fulcrum of this vision.

“If we can conquer space, we can conquer childhood hunger.”

– Buzz Aldrin.

But the future might not be all milk and honey. In a geopolitical climate once again taking the shape of a bipolar world, the two superpowers, the United States and the People’s Republic of China, may seek to further their security competition through a new space race, potentially to Mars. A second Cold War could sink resources into both military pursuits and spacefaring capabilities, some of which might be repurposed in deadly directions. In any case, vicious competition might be the last thing we need to succeed on Mars and to solve the many crises humanity faces.

Conclusion

From ancient history to the present, Mars has had the potential to unite humanity and tear us apart. Its blood-red surface inspired wars spurred technological innovation and served as a location for the Opportunity rover’s heart-rending shutdown. Will the dream of Mars take precedence to solving the problems we already face, and doom us to an increasingly perilous journey on Earth? Will security competition intensify to new heights? Or will we find the sense and reason to collaborate? We will find out soon enough.

References

[1] NASA Science. (2024). Mars: Facts. science.nasa.gov

[2] Belmonte, J. L. (2019). Nergal: the shaping of the god Mars in Sumer, Assyria, and Babylon. University of Wales Trinity Saint David. academia.edu

[3] The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (1999, May 4). Mars | Roman Mythology, Symbols & Powers. Encyclopedia Britannica. britannica.com

[4] Sun, X. (2009). Connecting Heaven and Man: The role of astronomy in ancient Chinese society and culture. Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union, 5(S260), 98–106. doi.org/10.1017/s1743921311002195

[5] Falk, S. (2020, May 13). Masculine Mars? Planetary degrees in medieval astrology. Seb Falk. sebfalk.com

[6] Keene, B. C. (2022, January 20). Written in The Stars: Astronomy and Astrology in medieval manuscripts. Smarthistory. smarthistory.org

[7] Plant. D. (1995). Johannes Kepler and the Music of the Spheres. (1995). skyscript.co.uk

[8] Willett, N. (2020, December 21). The observational history of Mars as a pathway for a human mission. Marspedia. marspedia.org/

[9] Lomberg, J. (2020, July 23). Visions of Mars: then and now. The Planetary Society. planetary.org

[10] Masson, P. (2005, February 21). The history of Mars exploration. First Mars Express Science Conference.sci.esa.int

[11] Wall, M. (2018, September 26). A base on Mars? It could happen by 2028, Elon Musk says. Space.com. space.com

[12] Shindell, M. (2023). For the Love of Mars: A Human History of the Red Planet. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226821894[13] Handmer, C. (2020, May 11). The big question: Why go to space at all? Casey Handmer’s Blog. caseyhandmer.wordpress.com